BioSocial Health J. 1(4):220-232.

doi: 10.34172/bshj.39

Study Protocol

Community-based participatory process evaluation based on the Reach, Quality Control, Fidelity, Satisfaction, and Management (RQFSM) model in Nevada: A study protocol

Asma Awan Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

Manoj Sharma Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1, 2

Author information:

1Department Social and Behavioral Health, School of Public Health, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89119, USA

2Department of Internal Medicine, Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, 89154, USA

Abstract

Introduction:

The healthcare system in Nevada has rural-urban, racial-ethnic, economic, and other inequities in care. Social determinants of health (SDOH) have exacerbated health disparities among high-risk and underprivileged populations. This study protocol presents Nevada’s COVID-19 public health disparity reduction initiatives and community-based participatory process evaluation methodologies. The participatory process evaluation based on the Reach, Quality Control, Fidelity, Satisfaction, Management (RQFSM) Model has been planned with 25 partner organizations that deliver public health services within Nevada.

Methods:

This program evaluation will be conducted by the University of Nevada, School of Public Health in collaboration with the Nevada Office of Minority Health and Equity (NOMHE) and the State of Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health (DPBH), as primary agencies along with other partner organizations funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A mixed-methods approach will be implemented to collect data from 25 partner organizations. For assessing the reach, quantitative and qualitative quarterly data collection reporting forms and focus group discussion (FGD) protocols will be designed; for quality control, fidelity, and management, semi-structured interviews and FGDs of project personnel and community members and process observation tally sheets will be generated, and for consumer satisfaction assessment, quantitative satisfaction surveys will be created in a participatory manner with all stakeholders.

Results:

The results of the protocol explain that community-based initiatives offer comprehensive, culturally competent, and high-quality primary healthcare services, while community health centers and other private sector groups can be considered as essential connections. Furthermore, it is anticipated that the necessity to integrate services like mental health, drug addiction treatment, pharmacies, disability assistance, and health care for older individuals would be acknowledged. This integration will be particularly crucial in places where access to reasonably priced healthcare is hampered by cultural, geographic, or economic restrictions.

Conclusion:

In this study, we describe the protocols of this community-based participatory process evaluation based on the RQFSM Model in Nevada.

Keywords: Social determinants of health (SDOH), RQFSM Model, Mixed-methods approach, COVID-19, Thematic analysis

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Authors.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

This project has received funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Public Health Disparity Grant for the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. This program evaluation falls under the Division of Public and Behavioral Health (DPBH) which is an identified eligible agency to submit for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities funding opportunity (CDC Health Initiatives Program).

Introduction

Post-COVID-19 era and health disparities

The healthcare sector faced a significant number of difficulties in motivating, improving, and monitoring personal behaviors for COVID-19 prevention, particularly considering the outbreak of the pandemic and the immediate post-pandemic years. Presently, the pandemic has been distinguished by imperceptible transmission networks, a heightened number of asymptomatic carriers, and community outbreaks. A robust 3-year community-based participatory evaluation (CBPE) program in Nevada has been planned using protocols that have been developed for a mixed method approach for community interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs), staff interviews, and process observation tools based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) grant guidelines.1 The protocols have been developed and approved by all stakeholders including the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Nevada Office of Minority Health and Equity (NOMHE) which contextualized and proposed guidelines for program creation, activity execution, and assessment strategies.

CBPE is a valuable approach for community organizations to tailor programs to the specific needs of their populations. This method involves collaborative, egalitarian, and partnership processes between researchers and participant groups to assess, define, solve, evaluate, and disseminate issues chosen by stakeholders.2 It emphasizes the importance of involving everyone in the program in the evaluation process, setting objectives jointly, addressing difficulties collectively, and raising awareness collectively.3 Studies have shown that community-based participatory research (CBPR) is grounded in collaboration, community wisdom, shared ownership of research procedures, intervention design, evaluation, and application.4 This approach has been increasingly recognized as a potent method for addressing health disparities and promoting health equity.5 Furthermore, participatory evaluation strategies advocate for local community groups and coalitions to identify potential outcomes or indicators of change, thus enhancing the relevance and effectiveness of interventions.6 Although there has been a significant rise in health disparities globally over the past 50 years, disparities in research and evaluation among different still persist, and may even be growing, particularly in relation to national income groups.7 The exceptional differentials that have become apparent in recent worldwide health crises, particularly the COVID-19 pandemic, have emphasized the crucial requirement for efficient public health interventions, fair distribution of healthcare mechanisms, and a more profound comprehension of the socio-economic factors that contribute to global health inequalities.8 Global health, when extrapolated to community health furnishes policy reforms and future research areas that aim to promote more resilient public health systems and reduce the health equality gap.

Implementing participatory evaluation in community-based programs is feasible and effective, contributing to capacity building, sustainability, and empowerment within communities.7,8 It is crucial to monitor and maintain CBPR activities throughout the evaluation process to identify and leverage their influence within partnerships.9 Additionally, utilizing methods of program implementation can help understand the context and impacts of community-based health programs, especially in situations where changes occur beyond the individual level.10 Anticipated enhancements are expected in the results of susceptible and high-risk populations. The implementation of better preventive measures and increased adoption of vaccines are projected to reduce disparities in disease contraction and prevalence.10

The proposed strategies for the current process evaluation utilizing the Reach, Quality, Fidelity, Satisfaction, Management (RQFSM) Model11 evolved over time to strengthen the connections between community health and evaluation while collectively leveraging the efforts and employing participatory training. The concept has come forth from the seminal work presented by Sharma and Bhatia,12 which combined the modern paradigms to advocate for marginalized groups, integrate health behavior interventions, work with government entities on planning and implementation, and prevent duplication, without commercialization for international networks. Later the initial model implemented for a case study in the community-based rehabilitation (CBR) program identified difficulties in the assessment of coverage, accessibility, and impact on the lives of persons with disabilities (PWD) in a rural population.13 Other external factors contributed toward enhancing the function of participatory processes for organizations to represent PWD in advocating actions and safeguarding their human rights.14,15

Health disparities in Nevada

Health disparities in Nevada are a pressing issue that necessitates attention and action to tackle the root causes and enhance health outcomes for all demographic groups. Nevada exhibits notable health differences. These disparities can be attributed to the significant geographical distances and demographic imbalance between the state’s two primary urban regions (Clark and Washoe counties) and the other 14 counties. This might lead to insufficient resources or limited access to essential services, such as healthcare providers, medical facilities, safe pedestrian areas, or fresh food options.16 Among the Nevada population, American Indians, Asian Pacific Islanders, and non-Hispanic Blacks are demographic groups that commonly experience these health issues. The enhanced availability of nutritious foods and fresh produce heightened physical activity and mobility, and regular visits to healthcare providers for preventive or routine examinations can help prevent numerous chronic illnesses. Research has identified several health challenges in Nevada, including low colorectal cancer survival rates,17 high incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome,18 and disparities in access to oral health care.19 These disparities are influenced by factors such as race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic location, underscoring the importance of targeted interventions to mitigate inequities.

Community-based participatory models with a focus on enhancing evaluation together with adaptability to research have emerged as effective approaches to collectively investigate and address health disparities.5,20 By engaging community members, organizational representatives, and researchers in all stages of the research and evaluation processes, CBPR and CBPE can help tackle social, structural, and environmental inequities that contribute to health disparities.21,22 Before the onset of COVID-19, there were notable disparities between racial and ethnic groups in Nevada. These disparities encompassed various aspects, such as elevated poverty rates, lower rates of high school completion, limited access to healthcare and nutritious food, and increased prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, and infant mortality.23,24 These disparities illustrate the adverse effects of persistent inequalities in the social determinants of health (SDOH), which heightened the vulnerability to contagious diseases such as COVID-19 and the inequitable impact of COVID-19, disproportionately affecting minority populations and high-risk, underserved groups at a significantly higher proportion.25

Accurate information in emergency responses should be prioritized for populations that are most susceptible to COVID-19. Moreover, the presence of long-term stressors, in conjunction with the COVID-19 pandemic and even post-pandemic, collectively intensified feelings of fear, anxiety, and social isolation among individuals who experienced racism and discrimination with exacerbation of psychosocial stress in these communities.26,27 Expanding the scope of program evaluation to incorporate program planning can further enhance the contributions it makes to enhancing intervention programs.28,29 Our study also argues that obstacles to conducting participatory plan evaluations can impede endeavors in CBPE. We have proposed solutions to tackle these issues and aim to stimulate further research in these domains.

Moreover, understanding the effects of policies and interventions on health disparities is paramount. For example, the implementation of policies such as the Nevada Indoor Clean Air Act has been linked to significant reductions in the incidence and mortality rates of esophageal and lung cancer, highlighting the importance of public health policies in addressing disparities.30 Nevada decision-makers devise strategies and policies to address COVID-19’s underlying conditions and direct health and economic impacts on communities of color.31 Addressing health disparities in Nevada demands a comprehensive approach involving community engagement, policy interventions, and targeted research endeavors. By implementing strategies such as CBPR, monitoring policy impacts, and focusing on specific health areas with disparities, progress can be made toward achieving health equity and enhancing health outcomes for all individuals in Nevada.

Background—Initiative

As of May 2023, more than 600 million vaccinations have been given in the United States, and over 5 million COVID-19 shots have been given in Nevada, by the CDC.32 Not only has the global pandemic had severe effects on a global scale, but it has also highlighted some inequalities in the healthcare system. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a substantial negative impact on communities of color. This project aimed to implement a strategic framework to evaluate public health disparity reduction efforts in Nevada. In Nevada, COVID-19 incidence varies by race and ethnicity. White people account for approximately 51% of all COVID-19 deaths, which is comparable to their demographic proportion.33,34 African Americans make up approximately 9% of Nevada’s population and account for 8% of COVID-19 cases. Despite comprising only 9% of the state’s population, Asian Americans account for approximately 12% of deaths and 7% of COVID cases.34 Latinos in Nevada were exposed to COVID-19 in greater numbers than those in the general population. While Latinos comprise 30% of the state’s population, they account for 40% of cases and approximately 22% of deaths.34

The health system in Nevada is structured in a way that identifies a lot of disparities in the ways that care is accessed and delivered. For example, there is a large disconnect between rural and urban healthcare systems, a wide gap in the logistics for the underserved populations of racial and ethnic minorities, and the unequal burden of morbidity and mortality due to the disproportionate severity of COVID-19 compared with national indicators. Community partnerships with key organizations began proliferating in 1996 to assist in promoting public education through the distribution of materials, providing community support, and participation in coalition-sponsored events.31 The community partnerships provided education, awareness activities, programming, and resources to address health disparities in different communities.

Understanding the accessibility and needs of diverse populations towards the public health system and population factors such as socioeconomic demographics will improve efforts to increase affordability and access to health care. The consequences for not addressing healthcare access issues include deteriorating health and well-being for vulnerable socio-demographic groups in the state.35 Altogether, these findings suggest that programs and policies within the state must be sensitive to the specific needs of at-risk groups, including minorities, those with low income, and regionally and linguistically isolated residents.

It is foreseen that the set of tools described below will address the weaknesses highlighted above. These evaluations will encompass a range of quantitative and qualitative methodologies including surveys, log sheets, checklists, observational tools, interviews, and FGDs.36 By employing qualitative methods such as participant interviews and direct observation of persons’ daily activities, researchers will obtain significant insights throughout the process evaluation.37 This will enable the investigation of complex cause-and-effect relationships, improve the understanding of how things are put into action, and capture a wide range of experiences with interventions. As a result, it will generate new ideas that may influence decision-making. Process evaluation will entail a wide spectrum of activities about the program and people including monitoring and documenting an intervention’s execution and comparing it to the program plan;38 helping evaluate the intervention’s efficacy, identifying obstacles, and reifying the solutions;39 and understanding the complexity of interventions in non-linear program implementation.40

The Reach, Quality, Fidelity, Satisfaction, Management (RQFSM) model of process evaluation

Process evaluation is a type of program evaluation that uses descriptive and analytical research methods to evaluate the program being implemented with the program initially planned by organizers.41 Process evaluation effectively complements other types of program evaluation.42,43 Importantly, it provides program authors and evaluators with a more comprehensive grasp of a program’s concept, execution, and operation. Process evaluation is a method used in program assessment to determine how well a program’s implementation aligns with the intended protocol.44 It functions as a powerful instrument for program developers and assessors, offering significant insights into both program design and implementation.

Additionally, it offers a valuable understanding of the program’s structural and delivery aspects, as well as improves the program creators’ and evaluators’ capacity to reproduce and articulate their programs to external entities. Process evaluation provides a comprehensive assessment of the services and activities. Significantly, it clarifies the factors that contribute to the attainment or non-attainment of desired results.11,12 The Medical Research Council’s Guidance on Process Evaluation of Complex Interventions highlights the significance of evaluating fidelity, quality of execution, causal mechanisms, and contextual factors that influence variations in outcomes.45

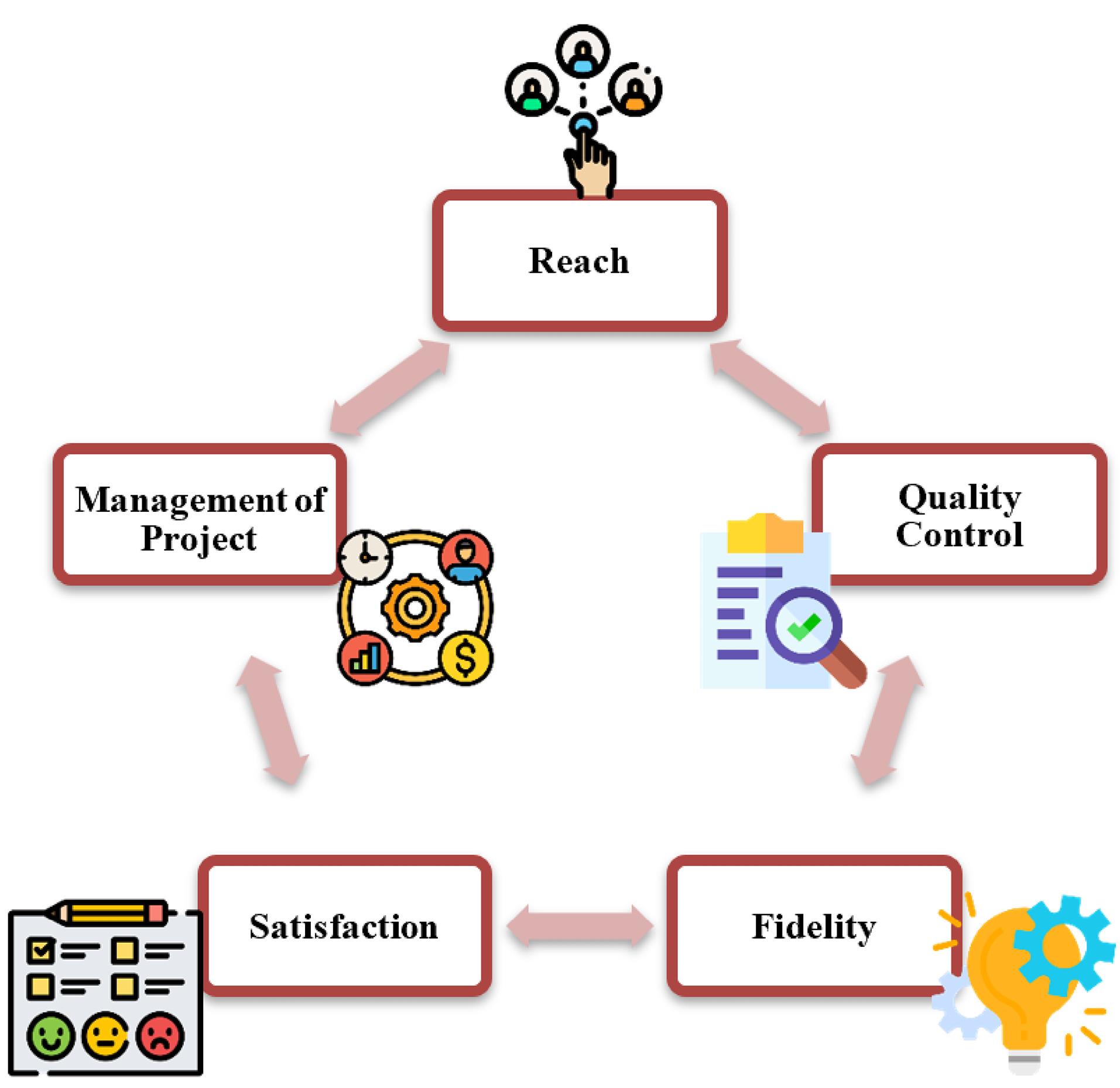

Our approach utilizing the participatory RQFSM Model described by program reach, quality control, implementation fidelity, consumer satisfaction, and program management (Figure 1) will emulate the paradigm of community-based activities from the data collection, description, and analytical techniques and will follow the participatory shift. The primary purpose of this process evaluation is to utilize evaluation data to guide programming policies and practices undertaken by the Health Disparity Grant in July 2021 from the CDC and administered by the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services through its Division of Public and Behavioral Health (DPBH). The DPBH is an identified, eligible agency that facilitated the broad CDC National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities, referred to as CDC Health Initiatives Program or Health Disparity Grant.1 The program strategies are enumerated as, (1) mitigation and prevention resources to reduce COVID-19 disparities, (2) improvements in data collection and reporting for COVID-19 disease variables, (3) infrastructure support processes for COVID-19 control, and (4) mobilization of health equity partnerships to reduce COVID-19 disparities. The protocols will employ a community-based participatory RQFSM Model developed and tested by Sharma11,14 to assess various aspects of the program. This work has had a concrete effect and has successfully identified disadvantaged populations through the implementation of grant strategies, in addition to promoting community care and awareness via community health workers. The model has been pilot-tested in North Central Vietnam and Mongolia for the process evaluation of CBR programs for PWDs13,14 and successfully enumerated the factors pertaining to socioeconomic stability in implementing successful CBR programs.

Figure 1.

The RQFSM Model. This figure shows how the 5 components of the RQFSM Model are interconnected and contribute toward the Process Evaluation

.

The RQFSM Model. This figure shows how the 5 components of the RQFSM Model are interconnected and contribute toward the Process Evaluation

Aims and objectives

In addition, the process evaluation presented will seek to uncover the contextual elements that will enhance prescribed implementation, increase our understanding of impactful components or activities, and permit intervention changes. As we are in the early stages of constructing the framework and the funding organization prohibited research activities, we would not employ any assessment of validity. Nevertheless, all the protocols have been formulated in accordance with the specified criteria and questions outlined by the creators of the framework. The evaluation of the content validity and concurrent validity of the RQFSM framework by psychometric testing is not within the scope of our study. The “process evaluation” developmental team has compiled, evaluated, and incorporated any comments and proposed edits to the evaluation protocols and instruments suggested by the partner organizations. The measures were determined through group discussions and iterations until a consensus is achieved. These elements have been used for process evaluation, integrating the needs of program planning, delivery, and changes.41 It also helps researchers understand complex intervention results, especially when implementation is nonlinear.43 In this way, process evaluation will show a program’s impact on the study environment by providing significant insights.

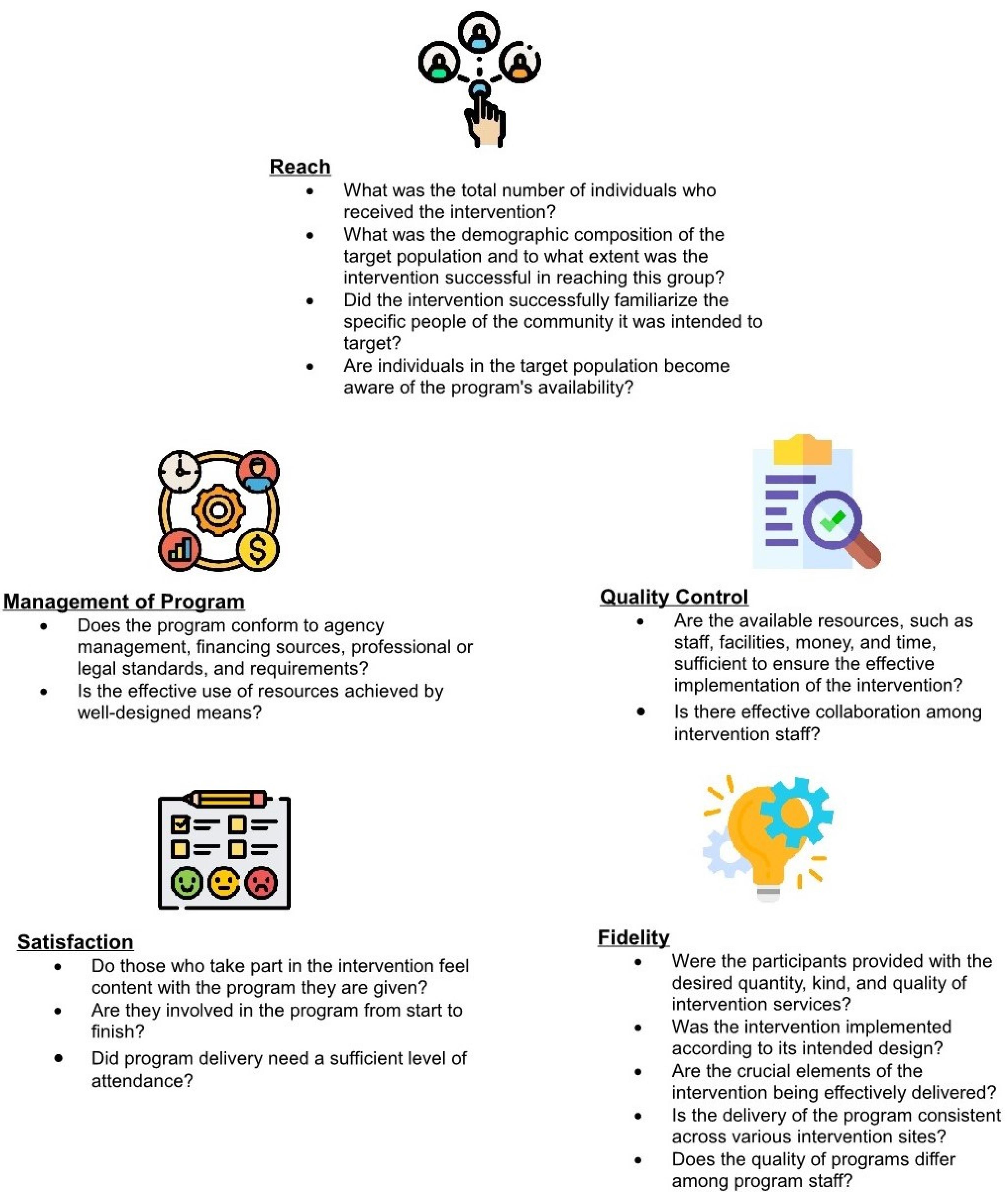

The purpose of our process evaluation is to provide essential data for informing program design, delivery, and adjustments (Figure 2). These modifications, aligned with the RQFSM Model, synergistically will be aimed to enhance program outcomes and long-term impacts. Interventions will be adjusted based on the RQFSM Model to improve outcomes while maintaining cost-effectiveness.11,12 In line with the RQFSM Model, modifications to interventions are envisaged to yield improved program outcomes while ensuring a satisfactory cost-benefit ratio. The core objectives of this program will be to enhance the nation’s public health infrastructure, guarantee an interconnected public health system, and facilitate the provision of core public health services by providing capacity-building support. The contextualized factors set as the four grant strategies and their subsequent twenty-eight activities under each strategy have been utilized as the study protocols mentioned in the proceeding sections.

Figure 2.

Target questions for the RQFSM Model. The figure explains tentative questions that be asked for all the target components in the RQFSM Process Evaluation

.

Target questions for the RQFSM Model. The figure explains tentative questions that be asked for all the target components in the RQFSM Process Evaluation

The design of a process evaluation requires flexibility to adapt to time and budget constraints. The notion is to creatively use different types of information that may be available to adapt to changes in project implementation and the changing environment in which the project will operate. The scope of work for the process evaluation of the CDC Public Health Disparity Grant will be expected to address the four strategies and their collective twenty-eight activities devised by the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services.

Materials and Methods

We will employ a multimethod approach with a convergent parallel design using multiple data sources. The mixed-methods approach is designed with the goals to take advantage of the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative data and to produce a more robust description and interpretation of the population characteristics under consideration (Table 1). In addition, the mixed-methods approach can expedite the process of translating a tested intervention into evidence-based interventions in real-life settings, which are often more intricate than the controlled environments where intervention research is typically conducted.46

Table 1.

Putative targets and methods for the RQFSM Model

|

Putative targets

|

Putative methods

|

|

Reach*

|

|

| How many participants were reached? |

Number of counts from reports submitted by units |

| Whether intended minorities reached? |

Descriptive demographics from reports submitted by units |

| Were any additional participants not intended reached? |

Descriptive demographics from reports submitted by units |

| Did the community members know the programs were available |

FGDs with community members |

|

Quality*

|

|

| Were resources (staff, facilities, money, time) adequate to support high-quality delivery? |

Interviews with program staff

FGDs with community members

Reports submitted by units |

| Did the intervention staff work effectively? |

Observations

Interviews with program staff

Reports submitted by units |

|

Fidelity*

|

|

| Were the project activities delivered as planned? |

Review of program reports

Checklists directed observations |

| Did the participants receive the intended amount, type, and quality of services? |

FGDs with community members

Interviews with community members

Review of program reports submitted by units |

| Were there any modifications from planned activities? |

FGDs with community

Interviews with community members |

| Were the essential components delivered well? |

Review of program reports submitted by units |

|

Satisfaction*

|

|

| Were the participants satisfied? |

Rating surveys

FGDs with community |

| Did the participants utilize all services? |

Interviews with community members |

| Was adherence adequate for project delivery? |

Interviews with program staff

Review of program reports submitted by units |

|

Management*

|

|

| Did the project comply with professional standards, funding agency requirements, legal standards, and agency administration? |

Review of program reports submitted by units

Interviews with program staff

Observations |

| Were the resources used efficiently? |

Review of program reports submitted by units

Interviews with program staff

Observations |

FGD, Focus group discussion.

*Putative targets and methods only give an example of the Process Evaluation based on RQFSM, but other methods can also be incorporated depending on the program's needs.

Evaluation questions

Our evaluation questions will focus on:

-

How much intervention will be provided and documented?

-

How well will the intervention be delivered to its intended audience?

-

Will the intervention be designed to address important questions regarding the delivery of health promotion?

-

How well the proposed RQFSM Model will fit the educational interventions and follow the devised logic model?

-

What will be the insights into a program and whether it will be effective or not?

-

How to enhance stakeholders’ abilities to interpret the impact and outcome evaluations of the same program?

-

How can the goals for a quality process evaluation be conducted efficiently and with minimum health program disruption?

Population and sample

Cross-sectional data will be collected from the 25 active community organizations as well as their counterpart state entities. Within these organizations, certain departments and personnel are expected to have been participating in health disparity grant initiatives directed toward high-risk and underserved populations. Other key informants and community individuals who have participated in the past will be interviewed using structured questionnaires. A total of 25 organizations are considered to have actively participated in the 3-year project. People who participated in the past in inactive communities will be recruited and interviewed in focus groups. These individuals will be contacted by the project coordinator and evaluators from these sites. Also, stakeholders responsible for the coordination or implementation of the program strategies and activities (i.e., stakeholders, supervisors of project coordinators, peer navigators, resilience ambassadors, and community health workers/instructors) at all current and former project organizations will be interviewed. Data collection will be carried out on program strategies which are enumerated as, (1) mitigation and prevention resources to reduce COVID-19 disparities, (2) improvements in data collection and reporting for COVID-19 disease variables, (3) infrastructure support processes for COVID-19 control, and (4) mobilization of health equity partnerships to reduce COVID-19 disparities.

Evaluation methodology – The RQFSM framework question insights

Program Reach

A set of questions has been curated with protocols to address whether the program is being delivered to the intended audience. It requires careful definition of the target audience of the program.

Quality control

It refers to the appropriateness of a set of professional activities employed to meet a set of objectives for the population under consideration. Quality standards, the minimum acceptable levels of performance used to judge the quality of professional practice, are also used to verify that professional standards are met in designing and implementing the health education or health promotion program.

Implementation fidelity

Fidelity ensures that the program is being delivered efficiently with another set of questions This is accomplished by evaluators and program delivery professionals who precisely identify the critical components of the program and then monitor its implementation. It increases the confidence with which one can assert that the program is delivered according to the plan.

Consumer satisfaction

The extent to which a health program meets or exceeds the expectations of participants, and the importance that consumers of health programs stay interested in and satisfied with the program they receive. The health program will be more effective in recruiting more participants if consumers are generally pleased with the health program interviews, focus groups, and surveys.

Program management

This refers to the program’s compliance with the requirements of professional standards, legal standards, funding agencies, and agency administration. Program accountability resides with the ability to document to stakeholders and sponsors that health programs are delivered as planned. The component of responsibility refers to health professionals ensuring that programs and services are delivered according to quality standards.

To align the evaluation interests of both the communities and funding entities, it is essential to integrate evaluation into each step of the RQFSM framework, rather than subjecting its individual components as an additional measurement factor. This will explain the utilization of a mixed-method approach that we will implement to enhance the convergence of data and interpretation of findings

Instrumentation and Protocols

After engaging in conversations with the state entities, community stakeholders, and partner organizations, it will be expected that the most effective approach for data collection would be to devise specific protocols for individual interviews from both the project personnel and community members, FGDs, and observation sheets, both in person and online. In addition, a robust mechanism for qualitative and quantitative data collection will be implemented through uniform quarterly reporting forms and annual/biannual satisfaction surveys. This will attain a higher degree of adaptability and an increased likelihood of participation from populations from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, gender categories, geographical distribution areas, and many other high-risk and underserved populations and communities within the state. Feedback on all protocols is planned to be obtained from the partner organizations’ personnel, community stakeholders, and peer support specialists in order to ensure validity, minimize potential obstacles to participation, and ensure that the questions will be advantageous to the communities. Most of the protocols will be implemented, and procedures will be carried out by or with the assistance of a peer support individual from the community.

Data collection

A process evaluation based on the RQFSM framework will be conducted using a mixed-methods approach, specifically employing a concurrent triangulation design. The objective of employing mixed methods is to validate the effectiveness results (triangulation and convergence) and to obtain valuable insights on the intervention, implementation, and context. This approach will overcome the inherent limitations of relying solely on quantitative or qualitative methods (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data collection methods

|

Data collection methods

|

Qualitative content

|

Quantitative content

|

| Processes observations |

|

|

A series of observations of partner

organizations’ events to assess the

engagement of the communities |

N = 5-6*

simple

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Compliance with guidelines

-

|

N = 5-6*

*Approximate number of observations conducted each quarter

Number of participants, age, race /ethnicity, gender, geographical distribution, number of resources and materials provided, number of information sessions, duration of activities/events |

| Project personnel interviews |

|

|

10-15 minutes of semi-structured

interviews to inform about the process

evaluation design, and

acquire information about key

facilitators and barriers |

N = 25*

simple

-

-

- Resource adequacy/ effectiveness

-

- Effective functionality

-

- Compliance with guidelines

|

N = 25*

*Approximate number of interviews conducted each quarter

Number of interviews conducted |

| Community members’ interviews |

|

|

| 10-15 minutes of semi-structured interviews to learn about the perceptions and activities of the project activities in which they have participated |

N = 15-20*

|

N = 15-20*

*Approximate number of interviews conducted each quarter

Type of high-risk, underserved group representation |

| FGDs |

|

|

45-60 minutes session with 5-8 people either from the communities or the stakeholders to learn about

opinions on the activities of the project, utilizing a combination of written, open/closed-ended questions, and/or narrow questions |

N = 5-7*

simple

-

-

- Experience with participation

-

-

-

-

-

|

N = 5-7*

*Approximate number of FGDs conducted each quarter

Number of participants in each focus group. |

| Uniform quarterly reporting forms |

|

|

| A standardized data reporting form submitted by all partner organizations every quarter to report their variables of services in the community and assigned activities |

N = 25*

simple

-

- Type of strategies and activities undertaken

-

- Type of settings served

-

- Resource adequacy/ effectiveness

-

- Modifications in activities

-

- Compliance with guidelines

-

- Adherence to Essential components

-

- Efficient use of resources

-

-

|

N = 25*

*Approximate number of forms

submitted by all organizations in each quarter

Number of strategies and activities undertaken, number of participants, age, race /ethnicity, gender, geographical distribution, number of settings served, number of resources and materials

provided, number of information

sessions/events held |

| Satisfaction survey |

|

|

Electronic and paper-pencil format survey disseminated in the state based on the quota of high-risk and under-served population, questions for

demographic and level of participant satisfaction with project activities

created on a Likert Scale of 0–4. Duration of 10-12 minutes |

N = 3-4*

with all the 4 strategies and their subsequent 28 activities

|

N = 3-4*

Approximate number of statewide surveys conducted under the evaluation activities in each year

Number of strategies and activities

undertaken, number of participants, age, race /ethnicity, gender,

geographical distribution, number of settings served, number of resources and materials provided, number of information sessions/events held, level of satisfaction |

*These numbers reflect the requirement of each data collection procedure based on the proposed protocol of community-based process evaluation.

Data analysis

Excel47 and SPSS 29.048 will be used to create data files for all qualitative and quantitative data. Furthermore, SPSS 29.0 will be used to run and analyze quantitative data. Descriptive statistics will be run for the demographic data, including the total number and percentage of participants from all high-risk and underserved populations. In addition, a chi-square test will be used to examine whether the observed results for different demographic variables are in order with the expected values. Assumptions for the data used in calculating a chi-square statistic will be checked for being random, raw, mutually exclusive, drawn from independent variables, and a sufficiently large sample. For the qualitative data, evaluators will transcribe the recorded FGDs and interview sessions in a word document. Participants will be anonymized by assigning them codes; for example, we will use combination code phrases for response questions in interviews and FGDs as P1.a-3/ReQ1 would represent participant 1, female, African American, response to question 1. We will use the NVivo 14 software49 for thematic analysis of the qualitative data. We will integrate the inductive methodology for coding the data which will be performed independently by two members of the research team. This will ensure the trustworthiness, credibility, and intercoder reliability of the qualitative analyses. After identifying the themes, these themes will be merged into final codes, based on the participants’ responses for each question drawing upon the components of the RQFSM Model. After the completion of the data analysis, the analysis will be shared with the partner organizations and community participants in the form of a report or quarterly deliverable.

Ethical considerations

This is a description of a protocol and as such no ethical approvals are needed at present. If the results are published, then appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals will be obtained.

Results

We seek a strong representation among racial/ethnic minorities, which would correspond well with our knowledge of how well the grant efforts have been reaching these populations. FGDs are expected to reveal that outreach to these groups would remain a significant challenge. Comparisons from all quarterly reports where the representation would not be as broad, improvements or deficiencies will be noted, or there will be results explaining how effectively closing the gaps would remain steady over time. Health outcomes will significantly reflect manageable factors, such as SDOH. To address these disparities effectively, it is crucial to refine our understanding of these determinants, including recognizing the negative systemic effects of racism as part of SDOH.

Community health centers and various organizations in the private sector will be considered to serve as crucial links for community-based programs that provide comprehensive, culturally competent, and high-quality primary healthcare services. Additionally, there is expected to be a recognized need to integrate services such as disability support, pharmacies, mental health, substance use disorder treatment, and health services for older adults. This integration will be considered especially important in areas where economic, geographic, or cultural barriers restrict access to affordable healthcare.

Population characteristics

It is crucial to recognize that different racial and ethnic groups will reflect unique needs and will require tailored representation. For instance, a diverse range of minority populations will require equal representation across subgroups. This will include people with disabilities, the LGBTQ + community, religious minorities, and other congregated housing. Similarly, American Indians, Black or African Americans, and Hispanic or Latino populations would have heightened needs among religious minorities. Asians, particularly those not born in the United States, would have faced specific challenges, while Native Hawaiians or Pacific Islanders would have encountered disadvantages in other conditions. These groups would have often lived in areas or facilities where social conditions would not be have been provided as equitable opportunities for health and well-being, making them disproportionately susceptible to diseases, dysfunction, and general illness.

Satisfaction survey findings

The Satisfaction Surveys will be expected to provide crucial insights into prioritized grant activities aiming at high-risk and underserved populations, identifying key issues that would need priority attention. A consensus will be built that communities could be viewed holistically, considering families and individuals collectively. This perspective will underscore the need for all organizations to address co-occurring conditions and comorbidities across various groups, including older adults aged 55-64, tribal nations or areas, correctional facilities or institutions, incarcerated individuals, other groups, and rural communities.

Community-based service providers would have offered both individual and collective support, along with comprehensive wrap-around services. For instance, among the Satisfaction Survey respondents, those who may have participated in the survey regarding public health disparity efforts would have lower satisfaction rates. The comparative shift in all surveys for all levels of satisfaction, under all categories would highlight the effectiveness and reach of grant activities in enhancing satisfaction among the targeted populations.

Focus group discussions themes

The analysis of FGDs will utilize both narrative descriptions and representative data extracts, such as direct quotations from the participants. This approach will inform on the rich context for data related to grant strategies and activities. The analysis described would offer a coherent argument explaining the context and outcomes of our Process Evaluation. Some narratives considered to be based on RQFSM components and generated independently will incite meaningful discussions. The FGDs analysis would generate benchmarks, objectives, and recommendations, which will provide insights into the success of the grant project within the analytical constructs of our RQFSM Model.

The project components identified throughout this effort will be meticulously grouped by themes based on the RQFSM Model. The analysis will include the effectiveness of community outreach efforts, challenges in delivering healthcare services, and the impact of grant activities on improving health disparities in the community. Moreover, FGDs could highlight the critical role of community engagement and the importance of tailoring interventions to meet the specific needs of diverse population groups. These discussions could also underscore the necessity of addressing language barriers, transportation issues, and other obstacles that hinder access to healthcare and other essential services. Participants’ need for continuous improvement and the importance of leveraging community knowledge and resources to develop sustainable solutions would be other linkages to understanding.

The FGDs analysis will provide valuable insights into the community’s perceptions and experiences with grant activities. The analysis based on the RQFSM Model will facilitate a deeper understanding of the successes and challenges of the project, guiding future actions and improvements. The thematic grouping of project components and the consideration of unique concerns will be envisaged as the groundwork for a more effective and responsive Process Evaluation framework, ultimately aiming to enhance the health and well-being of the community.

Implications

Process evaluation utilizing the RQFSM framework will provide comprehensive and inclusive strategies that may address the needs of each minority population. Implications derived from this process evaluation revisit a healthcare system of linguistic and cultural matching, incorporating culturally specific concepts, using culturally and linguistically adapted/appropriate written or visual material, and the involvement of families. The evaluation process if verified within organizations, will generate competency that relies on the concepts of cultural competency training, human resource development, integrating interpreter services, adapting to social and physical environments, and accurate data collection and management.

Health promotion and access are equally important, and evidence-based intervention strategies unique to underserved communities should be implemented according to their needs. A needs assessment accounting for perceived barriers, potential health disparities, and health inequity would be recognized as the pre-planning requisite to better recognize and serve all populations. Moreover, intersecting identities and demographic data will be considered to effectively provide specific resources to those who may experience difficulties in accessing healthcare in general.

The results from the process evaluation are predicted to emphasize community engagement to ensure that listening sessions would reach the target audience of political agencies and organizations at the local, state, and national levels can adapt once their needs are known. Instilling trust between healthcare providers and communities will foresee the impacts of satisfactory results when services are provided by opening opportunities for adjustments within organizations’ scope of work and funding prospects, together with anticipated outreach activities and incentives to build better communities.

Moreover, the restriction on funding might result in challenges in procuring necessary supplies and equipment, necessitating groups to seek alternate resources or form partnerships, especially in the context of community-based evaluation. One significant factor emphasized in the protocol development is to adhere to the pivotal role of healthcare personnel and services, particularly in rural regions. Nevada is predominantly rural, while healthcare services are primarily concentrated in urban regions, posing challenges for residents in rural towns to receive healthcare services.50 Furthermore, input from the key informants in the presence of language barriers, particularly among Spanish-speaking communities, would facilitate patients’ access to healthcare facilities in rural regions. Although there are foreseen factors related to financial assistance, especially maintaining sustained community partnerships, the key informants can play a vital role in describing the community level of achievement of the objectives, as seen in previous pilot studies utilizing the RQFSM process evaluation model.13,14

Our RQFSM framework process evaluation findings are perceived as a continuum to grow, collaborate, and participate in the good of the community. The RQFSM Model would serve as a guide and management tool for identifying meaningful outcomes, setting tangible measures, and evaluating cyclical processes.

Discussion

The RQFSM Model demonstrated and interpreted comprehensive program goals and methods that will be employed in the execution of process evaluation to address COVID-19-related health disparities and advance health equity.2 The project deliverables developed in the form of reports will generate evidence-based results of the purposes and objectives of process evaluations and will detail the specific measures and methods that can be used in the evaluation of other programs.4 The purpose of this evaluation will be to measure common foci, including all segments of the population when possible, and outline a system of service development and delivery.

When analyzing the current implementation of the RQFSM framework, a few components related to communication and the program approach to strategic planning will become apparent. Language barriers will be the most critical issue affecting both high-risk and underserved populations.17 Other anticipated indirect barriers to health care include transportation, language access, lack of trust, the costs of certain services, and more education about the health care system. In order to meet the objectives of process evaluation based on RQFSM, it is necessary to develop and refine each of the five essential competencies described under its five components. Also in future studies, we want to see a fully defined RQFSM framework to develop a robust process evaluation approach. Since it may not always be possible to capture the findings quantitatively, evaluation procedures often include a variety of methods including observation, feedback, interviews, and reflection. In situations when a certain kind of information is limited, the use of mixed methods might improve the overall evaluation.

Entities should have the ability to choose the best course of action that satisfies their specific needs, which can be implemented and sustained within current and anticipated resource constraints.20 Building on the cultural competency training will progress in the years to come and would incorporate the set of values and principles, and demonstrate behaviors, attitudes, policies, and acknowledge land that would enable the populations to work effectively cross-culturally. Process evaluation identified and created other foci for collaboration between like-minded agencies and community members. The common achievements of grant strategies and activities to improve the physical and mental health and overall well-being of communities can be explained by our RQFSM Model.38

Some limitations will foresee a need for continued funding sources and alternatives to incorporate process evaluation as an essential component in infrastructure projects, especially for underserved and high-risk populations for continued appropriations. The grant strategies and activities though gave a clear plan for the execution, yet their implementation and final analysis would yield futuristic goals and recommendations. Finally, solutions should have included initiatives throughout multiple sectors to identify and voice public health service issues and the SDOH.37,40 This limiting notion if resolved will make a positive impact on Nevada residents by thoughtfully following an evaluation-based system incorporating the RQFSM Model, i.e., reach, quality, fidelity, satisfaction, and management to improve the health and well-being of the under-served communities. The needs and capacities of the communities and available service providers that will emerge can be systematically evaluated in the Impact Evaluation phase.

Conclusion

Various comprehensive strategies have been implemented to facilitate community restoration in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. These strategies encompass areas such as healthcare accessibility, reopening of systems, cessation of preventive isolation measures, and the rollout of widespread vaccination campaigns. However, the healthcare system has remained in operation for the past two years and has consistently encountered notable difficulties. The lack of reliable and sufficient emergency finances has negatively affected shortages in healthcare, the ability to access healthcare, and the availability of healthcare facilities. It has also had a detrimental impact on the quality of the working environment of healthcare workers. As we go towards the period after the pandemic, it is essential to raise debates to the policy level to improve the health sector, which is in urgent need of a solution. Conducting assessments with underrepresented communities can be challenging, particularly when it comes to new initiatives, because of their intricate nature. The organization’s vision can only be achieved by employing proficient and committed experts in the relevant field, as well as by implementing effective and efficient project management. Given that certain firms would have progressively abandoned the project, organizations must demonstrate resourcefulness and flexibility by implementing essential improvements. The RQFSM project management principles allow for inquiry while providing the necessary guidance. Having these attributes enhances communication and operational efficiency in community-based collaborations, enabling leaders to make informed decisions by closely monitoring the progress of partner organizations and understanding the general direction of the project.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Data Availability Statement

Data collection methods and protocols are contained within the article

Ethical Approval

This is a description of a protocol and as such no ethical approvals are needed at present. If the results are published, then appropriate Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals will be obtained.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by the Nevada State Division of Public and Behavioral Health through Grant Number 1 NH75OT000092-01-00 from the CDC. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Division nor the CDC. Any activities performed under this sub-award shall acknowledge the funding was provided through the Division by Grant Number 1 NH75OT000092-01-00 from the CDC.

References

- CDC National Initiative to Address COVID-19 Health Disparities Among Populations at High-Risk and Underserved, Including Racial and Ethnic Minority Populations and Rural Communities Funding. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/funding/covid-19-health-disparities-ot21-2103.html. Accessed 26 August 26, 2024.

- Bomar PJ. Community-based participatory nursing research: a culturally focused case study. Jpn J Nurs Sci 2010; 7(1):1-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2010.00145.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Scarinci IC, Johnson RE, Hardy C, Marron J, Partridge EE. Planning and implementation of a participatory evaluation strategy: a viable approach in the evaluation of community-based participatory programs addressing cancer disparities. Eval Program Plann 2009; 32(3):221-8. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.01.001 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Simpson JE, Mendenhall TJ. Community-based participatory research with Indigenous youth: a critical review of literature. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 2022; 18(1):192-202. doi: 10.1177/11771801221089033 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health 2003; 93(8):1210-3. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 2006; 7(3):312-23. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Pericàs JM, Benach J. Inequalities in global health inequalities research: a 50-year bibliometric analysis (1966-2015). PLoS One 2018; 13(1):e0191901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191901 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al Ghamdi E, Alotaibi M, Alotaibi K, Alotaibi M, Alanazi F, Asiree AH. A comprehensive analysis of global health challenges: public health interventions, vaccine distribution hurdles, and the socio-economic roots of health disparities. Chelonian Research Foundation 2023; 18(1):272-82. [ Google Scholar]

- Simmons VN, Klasko LB, Fleming K, Koskan AM, Jackson NT, Noel-Thomas S. Participatory evaluation of a community-academic partnership to inform capacity-building and sustainability. Eval Program Plann 2015; 52:19-26. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.03.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Chávez JC, Rosario-Maldonado FJ, Torres JA, Ramos-Lucca A, Castro-Figueroa EM, Santiago L. Assessing acceptability, feasibility, and preliminary effectiveness of a community-based participatory research curriculum for community members: a contribution to the development of a community-academia research partnership. Health Equity 2018; 2(1):272-81. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0034 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Petosa RL. Measurement and Evaluation for Health Educators. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2014.

- Sharma M, Petosa RL. Evaluation and Measurement in Health Promotion. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass; 2023.

- Sharma M, Bhatia G. The voluntary community health movement in India: a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis. J Community Health 1996; 21(6):453-64. doi: 10.1007/bf01702605 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Deepak S. A participatory evaluation of community-based rehabilitation programme in North Central Vietnam. Disabil Rehabil 2001; 23(8):352-8. doi: 10.1080/09638280010005576 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sharma M, Deepak S. A case study of the community-based rehabilitation programme in Mongolia. Asia Pac Disabil Rehabil J 2002; 13(1):11-8. [ Google Scholar]

- University of Nevada, Reno. Health, is it Equal for All? Available from: https://www.unr.edu/nevada-today/news/2022/atp-health-disparities. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Callahan KE, Ponce CP, Cross CL, Sy FS, Pinheiro PS. Low colorectal cancer survival in the Mountain West state of Nevada: a population-based analysis. PLoS One 2019; 14(8):e0221337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221337 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Batra K, Cruz P, Cross CL, Bhandari N, Abdulla F, Pharr JR. Incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome epidemic and associated predictors in Nevada: a statewide audit, 2016-2018. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 18(1):232. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010232 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ditmyer M, Dounis G, Mobley C, Schwarz E. A case-control study of determinants for high and low dental caries prevalence in Nevada youth. BMC Oral Health 2010; 10:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-10-24 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Muhlisin A, Pratiwi A. Community-based participatory research to improve primary mental health services. Int J Res Med Sci 2017; 5(6):2524-8. doi: 10.18203/2320-6012.ijrms20172441 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Washburn LT, Traywick L, Thornton L, Vincent J, Brown T. Using ripple effects mapping to evaluate a community-based health program: perspectives of program implementers. Health Promot Pract 2020; 21(4):601-10. doi: 10.1177/1524839918804506 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cousins JB, Earl LM. The case for participatory evaluation. Educ Eval Policy Anal 1992; 14(4):397-418. doi: 10.3102/01623737014004397 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health 1998; 19:173-202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health. Nevada State Health Assessment (SHA). Available from: https://dpbh.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/dpbhnvgov/content/About/AdminSvcs/DPBH-SHA-2022.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2024.

- Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. Minority Health Report 2023. Available from: https://dhhs.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/dhhsnvgov/content/Programs/Office_of_Analytics/Minority%20Health%20Report%202023(1).pdf. Accessed June 8, 2024.

- Nevada Department of Health and Human Services. Nevada Office of Minority Health and Equity (NOMHE) Update on Nevada’s Health Disparities, 2020 Prepared for Nevada State Legislature, July 2020. Available from: https://dhhs.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/dhhsnvgov/content/Programs/CHA/MH/MH_Advisory_Committee/2020/NVHealthDisparities.pdf.

- Molassiotis A, Xie YJ, Leung AY, Ho GW, Li Y, Leung PH. A community-based participatory research approach to developing and testing social and behavioural interventions to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2: a protocol for the ‘COPAR for COVID’ programme of research with five interconnected studies in the Hong Kong context. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(20):13392. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192013392 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Haboush-Deloye A, Marquez E, Dunne R, Pharr JR. The importance of community voice: using community-based participatory research to understand the experiences of African American, Native American, and Latinx people during a pandemic. Prev Chronic Dis 2023; 20:E12. doi: 10.5888/pcd20.220152 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen HT, Morosanu L, Chen VH. Program plan evaluation: a participatory approach to bridge plan evaluation and program evaluation. Am J Eval 2024; 45(4):551-61. doi: 10.1177/10982140241231906 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Foote K, Foote D, Kingsley K. Surveillance of the incidence and mortality of oral and pharyngeal, esophageal, and lung cancer in Nevada: potential implications of the Nevada indoor clean air act. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(15):7966. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157966 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guinn Center for Policy Priorities. The Impact of COVID-19 on Communities of Color in Nevada. Available from: https://files.constantcontact.com/cb965190801/ef8b722c-06d7-4395-b585-e64e1f73dbea.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2024.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC COVID Data Tracker. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Solis J. Reports, Data Detail How Pandemic Exposes Long-Standing Nevada Inequities. Nevada Current; 2020. Available from: https://nevadacurrent.com/2020/09/02/reports-data-detail-how-pandemic-exposes-long-standing-nevada-inequities/. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Woodson JM, Braxton-Calhoun M, Black J, Marinelli R, O’Hair A, Constantino NL. Challenges of collaboration to address health disparities in the rapidly growing community of Las Vegas, Nevada. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009; 20(3):824-30. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0183 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson ND, Haff DR, Chino M. Health care access disparities among children entering kindergarten in Nevada. J Child Health Care 2013; 17(3):253-63. doi: 10.1177/1367493512461570 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract 2005; 6(2):134-47. doi: 10.1177/1524839904273387 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McGill E, Marks D, Er V, Penney T, Petticrew M, Egan M. Qualitative process evaluation from a complex systems perspective: a systematic review and framework for public health evaluators. PLoS Med 2020; 17(11):e1003368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003368 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nakkash RT, Alaouie H, Haddad P, El Hajj T, Salem H, Mahfoud Z. Process evaluation of a community-based mental health promotion intervention for refugee children. Health Educ Res 2012; 27(4):595-607. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr062 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Int J Nurs Stud 2013; 50(5):587-92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Limbani F, Goudge J, Joshi R, Maar MA, Miranda JJ, Oldenburg B. Process evaluation in the field: global learnings from seven implementation research hypertension projects in low-and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health 2019; 19(1):953. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7261-8 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stufflebeam DL, Shinkfield AJ. Systematic Evaluation: A Self-Instructional Guide to Theory and Practice (Evaluation in Education and Human Services). Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff; 1985.

- Judd CM. Multiple methods in program evaluation. In: Bickman L, ed. Using Program Theory in Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

- Scheirer MA. Designing and using process evaluation. In: Newcomer KE, Hatry HP, Wholey JS, eds. Handbook of Practical Program Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994. p. 40-68.

- Al Daccache M, Bardus M. Process evaluation. In: The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Social Marketing. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 1-4. 10.1007/978-3-030-14449-4_155-1.

- Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015; 350:h1258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. 2nd ed. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health; 2018. Available from: https://implementationscience-gacd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Best-Practices-for-Mixed-Methods-Research-in-the-Health-Sciences-2018-01-25-1.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Microsoft Excel. Available from: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- IBM SPSS Statistics. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- NVivo. Available from: https://lumivero.com/product/nvivo-14/. Accessed June 7, 2024.

- Nevada State Office of Rural Health. School of Medicine. Available from: https://med.unr.edu/rural-health. Accessed August 26, 2024.