BioSocial Health J. 1(4):197-203.

doi: 10.34172/bshj.47

Review Article

Determinants of delayed speech development in African immigrant children in Germany: A scoping review

Jude Tsafack Zefack Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, 1, 2, *

Favour Alo Adoche Investigation, Writing – original draft, 1, 3

Fuanyi Awatboh Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, 1, 4

Brenda Mbouamba Yankam Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1, 5, 6

Cynthia-Edith Ara-Nabangi Ndive Validation, Writing – review & editing, 1, 7

Esua Alphonsius Fotindong Writing – review & editing, 1, 8

Author information:

1Social Epidemiology Lab, Wuppertal, Germany

2Global Health and Bioethics, Engelhardt School of Global Health and Bioethics, Euclid University, Bangui, Central African Republic

3Benue State University, Benue, Nigeria

4Division of Clinical Epidemiology, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

5Department of Statistics, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria

6Malaria Consortium, Buea, Cameroon

7School of Public Health, Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium

8Applied Social Sciences, Technical University of Applied Sciences Würzburg-Schweinfurt, Wurzburg, Germany

Abstract

Introduction:

Delayed speech development is a prevalent global issue impacting children’s cognitive, social, and academic growth. However, limited research examines speech delays in African immigrant children, particularly in Germany. Cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic factors play crucial roles in language development within immigrant families. This review explores social determinants contributing to speech delays among African children in Germany and identifies research gaps for future interventions.

Methods:

A literature search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar, focusing on peer-reviewed studies from 2000-2024. Search terms included "Delayed speech," "Speech Development," "African immigrant children," "Socioeconomic factors," and "Germany." The review considered studies involving African children (aged 0–18) in Germany and the social determinants influencing speech delays.

Results:

African immigrant children in Germany face unique speech development challenges due to socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic factors. However, research and culturally adapted interventions are scarce, limiting understanding of the prevalence and impact. This review highlights a critical gap, with no targeted studies addressing speech delays in this population, underscoring the need for focused research.

Conclusion:

Socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic factors significantly impact speech development in African immigrant children in Germany. Early diagnosis and culturally sensitive interventions are crucial for better outcomes. This review identifies an ‘empty review,’ underscoring the urgent need for longitudinal studies, culturally adapted assessments, and policies to address social determinants and support targeted interventions for improved language development and integration.

Keywords: Delayed speech, Speech development, African immigrant children, Socioeconomic factors, Cultural factors, Germany

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Authors.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

This research has not been financed.

Introduction

The production of understandable sounds is known as speech.1 Verbal communication includes the following: Speech articulation, or the process of creating sounds; Vocal (using breathing and the vocal folds to make sounds); Fluency (the speaking pattern).2 Different forms of speech-language delays Language disorder receptive: Sharing thoughts, ideas, and feelings might be difficult for someone with expressive language disorder.2 Speech difficulties may arise from motor speech impairments (like dysarthria), anatomical differences (like cleft palate), or sensory deficiencies (like hearing loss). However, what caused most children’s articulation and phonological speech sound abnormalities was unclear.3 Risk factors include the male gender, prenatal and antenatal issues, oral sucking behaviours (such as excessive thumb or pacifier sucking), problems with the ears, nose, and throat, a more irritable temperament, a family history of speech and language disorders, low parental education, and a lack of encouragement for learning at home.3 In children between three and six, delayed speech and language development is the most prevalent developmental problem.

About 60% of speech and language delay cases in children under three years old tend to resolve independently. The condition has a frequency of 1 to 3.2% in the average population. This is due to the possibility that a child’s speech delay is the first sign of a behavioural, neurological, or psychiatric issue, or it might be a regular (and transient) developmental stage.3 “Delay in speech and language development compared with controls matched for age, sex, cultural background, and intelligence” defines delayed speech and language development in children.4,5 Speech or language impairment is a communication problem. Many children will need speech therapy to overcome their speech impediments.6 Roughly 5%–10% of kids suffer from developmental language difficulties. Their hallmark is severe difficulty learning a language without a known explanation, such as general mental retardation, physical infirmity, hearing loss, or a communication issue in general. Children with developmental language impairments are believed to be very susceptible to future behavioural, social, and academic problems. The results for impacted children may be improved by early detection and intervention. to evaluate children under seven for main speech-language delay.1 A child’s language development is integral to their growth and may significantly influence their social, emotional, and cognitive development.7,8 More studies on African children in Germany need to be conducted, despite studies looking at delayed speech in various groups. To provide specialised therapies and support, it is essential to comprehend the epidemiology of delayed speech in this population. In this demographic, delayed speech may be caused by various factors, including language challenges, cultural differences, and access to healthcare services. By reviewing available literature on the prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes associated with delayed speech in African children born in Germany, we can provide insights into existing research gaps and practical approaches to support early intervention and ideal language development in this target population.

Methods

Search strategy

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to identify studies on delayed speech in African children residing in Germany, focusing on socio-epidemiological factors. A search was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar, covering peer-reviewed studies published between 2000 and 2024. These databases were selected for their accessibility and inclusion of high-quality content relevant to both clinical and socio-epidemiological research. The primary search terms included “Delayed speech,” “Speech development,” “African immigrant children,” “Socioeconomic factors,” “Cultural factors,” and “Germany.”

Eligibility criteria

The review applied specific inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the selection of relevant studies. Studies were included if they focused on African children aged 0–18 living in Germany, emphasising speech and language delays and their relationship to social determinants such as socioeconomic status, cultural background, education levels, and healthcare access. The review considered observational studies, qualitative research on socio-cultural factors, and systematic reviews addressing speech delays, risk factors, and interventions. Only peer-reviewed studies from 2000–2024 were included.

Study selection

The study selection process involved multiple stages:

Title and abstract screening: Two independent reviewers initially screened titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles.

Full-text review: Full-text articles were retrieved for studies that met the inclusion criteria during the first screening stage. Discrepancies in study selection were resolved through consensus or consultation with a third reviewer.

Final inclusion: Only studies that met all criteria after the full-text review were included in the final analysis.

Results

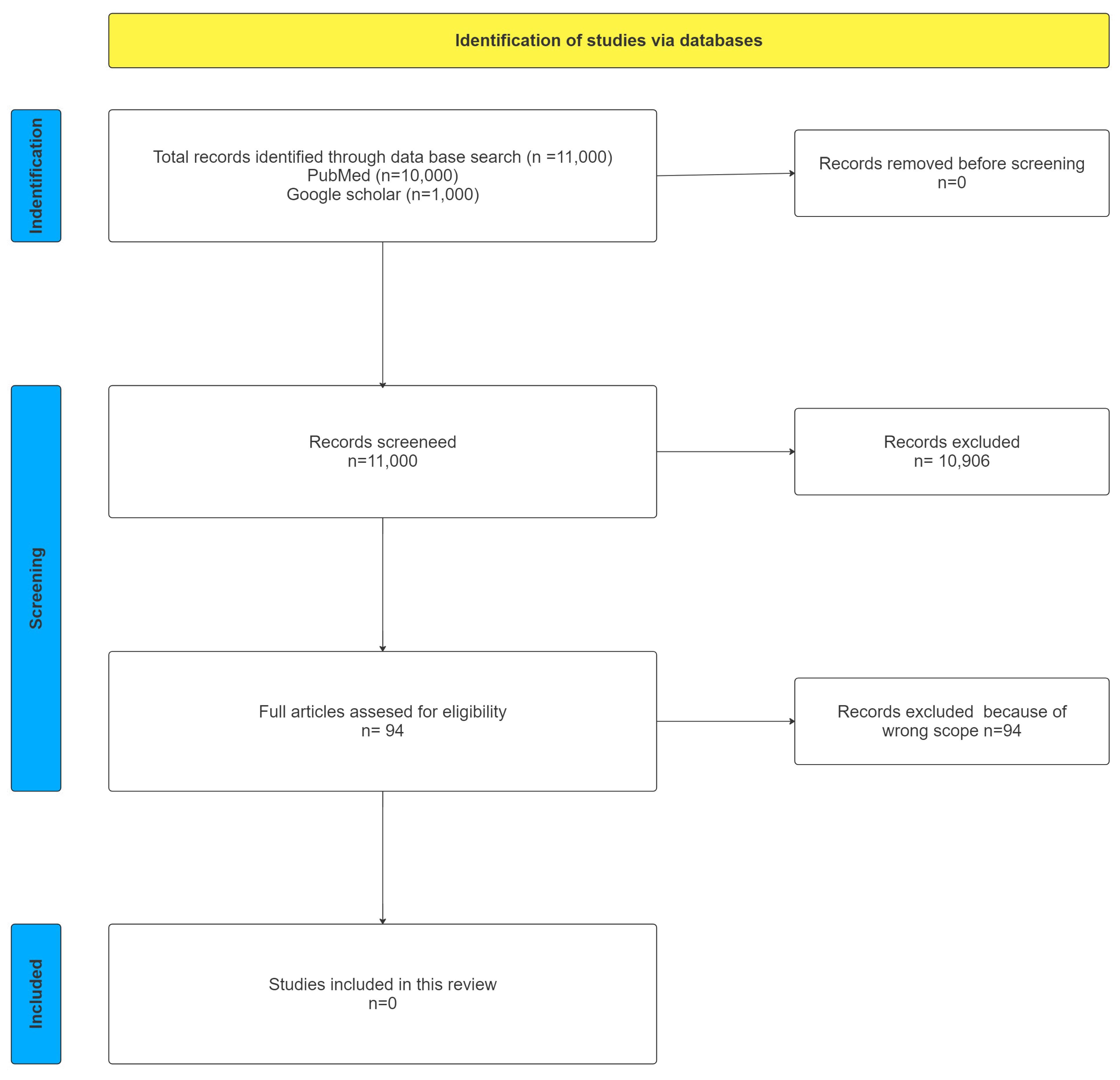

Figure 1 summarises the results of the search strategy employed in this scoping review. A total of 11 000 articles were identified: 10 000 from PubMed and 1000 from Google Scholar. After an initial screening, 10 906 articles were excluded based on their titles and/or abstracts, as they were deemed irrelevant to the review’s objectives. The remaining 94 articles were subjected to a full-text evaluation for eligibility; however, none fully met the predefined inclusion criteria. The search specifically aimed to identify studies focusing on African children aged 0–18 living in Germany, emphasising speech and language delays and associated socio-epidemiological factors. While none of the studies satisfied the inclusion criteria, the review revealed several key insights worthy of consideration.

-

No studies specifically targeted African children aged 0-18 residing in Germany with speech and language delays.

-

While some studies discussed socioeconomic factors and cultural backgrounds about speech and language development, none addressed these issues specifically for African children in Germany.

-

Many of the listed studies were reviews or general discussions rather than the specific types of studies outlined in our inclusion criteria (observational studies, randomised controlled trials, qualitative studies, or systematic reviews).

-

Several studies discussed speech and language delays but did not focus on the specific risk factors of interest (e.g., family environment, migration status, healthcare access) for African children in Germany.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram describing the selection process

.

PRISMA flow diagram describing the selection process

The most relevant study identified was that of Kasper et al, titled “Population-based screening of children for specific speech and language impairment in Germany: a systematic review.”9 However, this study did not specifically focus on African children or address the socio-cultural factors outlined in our inclusion criteria. These findings suggest a significant gap in the literature regarding speech and language delays among African children in Germany, particularly about socio-epidemiological factors. This gap highlights the need for targeted research in this area to understand better and address the unique challenges faced by this population.

Discussion

Factors contributing to delayed speech in migrant children

Multiple factors can impact the delayed speech of African migrant children in Germany. The linguistic environment at home, where parents can speak a language other than the community’s primary language, is one crucial element that contributes to speech development deficits. Socioeconomic circumstances can also cause speech delays,10 such as having access to educational materials and speech treatment facilities. Otitis media, often known as middle ear infection, is another risk factor as it can induce hearing loss and interfere with speech and language development.11 Oral sensory problems and oromotor dysfunction can result from sucking behaviours, such as utilising pacifiers, dummies, thumbs, or bottles.12 Cultural variations in expectations and communication techniques may also impact African children’s language development in a German environment. Moreover, the stress of acculturation and migration may be a factor in speech development delays. Comprehending these variables is essential to creating efficacious treatments to facilitate language acquisition in this demographic.

Cultural and linguistic considerations in speech development in migrant children

Several important professional documents such as the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Canadian Association of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists, and International Association of Logopedics and Phoniatrics) highlight the need for SLPs to work with children and families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in a culturally competent manner. The importance of culture, assessment of cross-cultural relations, vigilance towards the dynamics that result from cultural differences, expansion of cultural knowledge, and adaptation of services to meet culturally unique needs are all acknowledged and incorporated into culturally competent practice, according to the statement.13 Cultural and linguistic variety has been frequent in many civilisations worldwide due to increased international travel in recent decades.14 According to data from the United Nations Global Commission on International Migration, there were about 281 million foreign migrants worldwide in 2020.15 Many children from migrant households are seen as having various cultural and language backgrounds. This covers groups and families that may have immigrated to a nation several generations ago and recent immigrants. Families may choose to migrate voluntarily in search of better social or economic possibilities in a new country or be forced to relocate because of a war or other natural disaster. Families moving to a new nation must deal with various problems, including losing their identity, position, and ties to their community and family.16 Language and cultural preservation are vital means immigrant families keep ties to their homeland and sense of self. Like this, the upkeep of culture and language supports the identity preservation and continuation of Indigenous people whose territories have been colonised.17 To help children establish a sense of self and cultural identity, promoting their cultural and linguistic variety as they grow in speech, language, and communication is crucial.18

Furthermore, the impact of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion (JEDI) initiatives in the field of speech-language pathology must be acknowledged when examining the intersection of linguistic and cultural factors in speech development, especially among African children born in Germany, due to the difficulties in creating materials and interventions that are culturally sensitive at the macro level and the dearth of research on the needs of diverse patient populations.19 These factors highlight the need for customised approaches that consider cultural norms and values. Additionally, bilingual SLPs’ perspectives underscore experts’ complex experiences managing linguistic heterogeneity and promoting inclusive approaches.20 A more equitable and prosperous healthcare strategy for African children in Germany can be achieved by incorporating these viewpoints into approaches that address inequalities in speech development outcomes across varied communities, improve clinical competency, and encourage cultural humility.

Impact of delayed speech on academic and social development in migrant children

African children born in Germany and experiencing delayed speech could see their social and intellectual growth impacted negatively. Academically speaking, delayed speech can make it more difficult for a kid to interact with peers and teachers, making it harder for them to grasp instructions, participate in class discussions, and express their opinions. Lower academic achievement and even learning problems may follow from this. Socially, kids who have delayed speech could find it hard to build relationships with their classmates, feel lonely and frustrated, and find it hard to participate in social activities. These obstacles may influence their sense of self and well-being, resulting in long-term social and mental health problems.21,22 Therefore, early detection and intervention for delayed speech are essential to promoting the academic and social development of African children born in Germany.

Interventions and support strategies

Suppose an intervention is not pertinent to the individual receiving it or their ability to participate in their own life practically. In that case, it has no intrinsic worth. A comprehensive vision of each child is necessary for practice to be relevant and culturally competent. This is accomplished by considering the personal and contextual influences that affect how they operate and engage in society and their more extensive social and cultural background. Goals and recommendations for rethinking culturally appropriate practices in speech-language pathology were developed with input from global specialists.13 These suggestions emphasized the need to expand current practices to include:

-

SLPs recognise the impact of language and cultural factors on children’s lives and conduct accurate and appropriate assessments of children’s needs and strengths.

-

Utilizing multiple data sources to determine whether a speech, language, or communication issue exists.

-

Determining the impact of such an issue on children’s day-to-day activities.

-

Consult with appropriate collaborators (parents and teachers) to identify and implement proper strategies to support children’s development and increase their capacity for day-to-day functioning skills.

Applying these recommendations to promote holistic practice ensures that services and interventions are tailored to meet children’s needs, fostering optimal daily engagement. Furthermore, various global initiatives in speech-language pathology are advancing the adoption of culturally appropriate practices. Key examples of these efforts include:

-

Creating assessment instruments in various languages enables children to be evaluated in their native tongue instead of just the language or languages in which the SLP is proficient.23

-

Alternative evaluation methods include dynamic assessment.24 and parental or adult target contrastive analysis.25

-

Specialized university programs in speech-language pathology are devoted to multilingual and multicultural practice.

Also, various web-based tools have been created to assist SLPs in working with children who speak more than one language. These consist of screening instruments available in several languages to determine if a thorough evaluation of a child’s communication skills is necessary.26 and downloadable language structure and component information to help SLPs distinguish between a language difference brought on by various linguistic impacts on a child’s communication and an actual speech, language, or communication challenge.27 Furthermore, children in Germany and worldwide have succeeded with speech therapy, language development workshops, and personalised support in overcoming speech impairments.28 However, financial, linguistic, and cultural challenges may make it difficult for African children to obtain these programs. To deliver culturally aware and linguistically appropriate therapies that are specifically suited to the requirements of African children with delayed speech, healthcare professionals and educators must collaborate closely with families. We can enhance the general well-being and intellectual achievement of African children in Germany who have delayed speech by removing these obstacles and offering focused assistance.

Challenges in diagnosis and early intervention

Finding a balance between the preservation of families’ native tongue and culture and what is deemed essential acculturation to the prevailing context—including knowledge of the majority culture and proficiency in the mainstream language—can be challenging for both parents and SLPs. It is well known that regular encounters between two or more cultures lead to adopting characteristics from each culture, which influences the original cultures. It is critical to distinguish between assimilation, replacing one’s first culture with a second, and acculturation, which is gaining a second culture.13 Thus, dialogue, understanding, and collaboration between all parties involved in children’s development (including teachers, parents, SLPs, and the children themselves) are required to identify goals that enable children to maximise their participation in multiple cultural spaces in the academic and social domains. When children have speech, language, or communication challenges, supporting them to become proficient communicators can be challenging. In addition to the numerous difficulties that SLPs have documented—as was previously indicated—there are additional problems that come from disparate cultural perspectives, explanatory models, and interpretations of impairment.29 Diagnostic labels, such as specific language impairment and speech-sound disorder, are frequently used in Western cultures.30 However, they may not be appropriate in other cultures. They can negatively affect SLPs’ ability to establish rapport with families and create goals to motivate both parties to support children’s speech, language, and communication development. Consequently, culturally appropriate practice is essential for SLPs.13

As mentioned above, SLPs encounter multiple challenges while trying to provide services to linguistically and culturally diverse populations. Some of these are the lack of culturally appropriate assessment tools, developmental norms for linguistically diverse populations, service provision in children’s primary languages, professional support and training for working with families from diverse cultural backgrounds, and enough time to implement additional practice elements recommended for working with diverse families.31-37 Nevertheless, more information about realistic methods for overcoming these obstacles has yet to be released. Professionals in speech-language pathology are frequently guided toward the gold standard approach to implementing practice for specific patient populations or conditions.38 The challenge in determining and putting into practice a single gold standard approach for working with culturally and linguistically diverse populations is that it often results in practices that are homogenised according to the dominant culture, which ignores the diversity, complexity, and strengths that SLPs work with on behalf of their clients’ individuals and families.39

Strengths and limitations

This review explores socio-epidemiological factors contributing to delayed speech development in African children residing in Germany, filling a significant knowledge gap in existing literature. It integrates findings on socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic factors, drawing attention to the unique challenges this demographic faces. However, the review also highlights certain limitations in the field of study. There needs to be more empirical data directly addressing African children in Germany, particularly about delayed speech. While the review sheds light on relevant issues, more specific cohort studies, observational research, and culturally nuanced assessments are needed to allow the ability to draw robust, evidence-based conclusions. The scarcity of research that includes intersectional factors such as healthcare access, migration status, and family environment further emphasises the need for a more targeted approach to future studies.

Conclusion, implications, and future directions

The lack of empirical data on African immigrant children in Germany highlights an urgent need for longitudinal and intersectional research. This review, as an ‘empty review,’ underscores the critical issue of delayed speech development in this population and the absence of direct studies addressing it. This gap necessitates robust research efforts to provide actionable insights. Early diagnosis and culturally sensitive interventions are vital for improving affected children’s social, academic, and emotional outcomes. However, the absence of targeted studies limits the development of effective, culturally adapted therapies. Future research should focus on longitudinal cohort studies using culturally and linguistically relevant tools to better understand the prevalence and impact of speech delays. To bridge this gap, clinical and public health policies must evolve to support targeted interventions. Enhancing collaboration between healthcare providers and African families can promote optimal language development and social integration for these children.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all researchers whose articles were reviewed in the study.

References

- Mondal N, Bhat BV, Plakkal N, Thulasingam M, Ajayan P, Poorna DR. Prevalence and risk factors of speech and language delay in children less than three years of age. J Compr Pediatr 2016; 7(2):e33173. doi: 10.17795/compreped-33173 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Busari JO, Weggelaar NM. How to investigate and manage the child who is slow to speak. BMJ 2004; 328(7434):272-6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7434.272 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. CDC; 2024. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/index.html.

- Brunnegård K, Lohmander A. A cross-sectional study of speech in 10-year-old children with cleft palate: results and issues of rater reliability. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2007; 44(1):33-44. doi: 10.1597/05-164 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sachse S, Von Suchodoletz W. Early identification of language delay by direct language assessment or parent report?. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2008; 29(1):34-41. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318146902a [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). What is a Developmental Milestone? CDC; 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html.

- Shriberg LD, Kent RD, Karlsson HB, McSweeny JL, Nadler CJ, Brown RL. A diagnostic marker for speech delay associated with otitis media with effusion: backing of obstruents. Clin Linguist Phon 2003; 17(7):529-47. doi: 10.1080/0269920031000138132 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wooles N, Swann J, Hoskison E. Speech and language delay in children: a case to learn from. Br J Gen Pract 2018; 68(666):47-8. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X694373 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kasper J, Kreis J, Scheibler F, Möller D, Skipka G, Lange S. Population-based screening of children for specific speech and language impairment in Germany: a systematic review. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2011; 63(5):247-63. doi: 10.1159/000321000 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Zubair M, Gulraiz A, Kalla S, Khan S, Patel S. An assessment of risk factors of delayed speech and language in children: a cross-sectional study. Cureus 2022; 14(9):e29623. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29623 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani LD, Aldharman SS, Almuzaini AS, Aljishi AA, Alrabiah NM, Binshalhoub FH. Prevalence and risk factors of speech delay in children less than seven years old in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023; 15(11):e48567. doi: 10.7759/cureus.48567 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thorpe K, Rutter M, Greenwood R. Twins as a natural experiment to study the causes of mild language delay: II: family interaction risk factors. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003; 44(3):342-55. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00126 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Verdon S, McLeod S, Wong S. Supporting culturally and linguistically diverse children with speech, language and communication needs: overarching principles, individual approaches. J Commun Disord 2015; 58:74-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2015.10.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ottaviano GI, Peri G. The economic value of cultural diversity: evidence from US cities. J Econ Geogr 2006; 6(1):9-44. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbi002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). Interactive World Migration Report 2022. Available from: https://www.iom.int/wmr/interactive.

- Fillmore LW. When learning a second language means losing the first. Early Child Res Q 1991; 6(3):323-46. doi: 10.1016/s0885-2006(05)80059-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Williams ST. Recover, Re-Voice, Re-Practice. Sydney, Australia: NSW AECG Incorporated; 2013.

- Park SM, Sarkar M. Parents’ attitudes toward heritage language maintenance for their children and their efforts to help their children maintain the heritage language: a case study of Korean-Canadian immigrants. Lang Cult Curric 2007; 20(3):223-35. doi: 10.2167/lcc337.0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Moonsammy SU, Procter T, Goodwin ME, Crumpton P. Proactive strategies for breaking barriers: advancing justice initiatives in speech-language pathology for diverse populations in voice management and upper airway disorders. Perspect ASHA Spec Interest Groups 2024; 9(5):1290-300. doi: 10.1044/2023_persp-23-00138 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gréaux M, Gibson JL, Katsos N. `It’s not just linguistically, there’s much more going on’: the experiences and practices of bilingual paediatric speech and language therapists in the UK. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2024; 59(5):1715-33. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.13027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sherred L. How Communication Issues Can Impact a Child’s Social and Emotional Well-being. Expressable; 2020. Available from: https://www.expressable.com/learning-center/social-emotional-academic/how-communication-issues-can-impact-a-childs-social-and-emotional-well-being. Accessed April 24, 2024.

- Heuser Hearing Institute. The Effect of Communication Delays on Academic Performance. Heuser Hearing Institute; 2016. Available from: https://thehearinginstitute.org/the-effect-of-communication-delays-on-academic-performance. Accessed April 24, 2024.

- McLeod S, Verdon S. A review of 30 speech assessments in 19 languages other than English. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2014; 23(4):708-23. doi: 10.1044/2014_ajslp-13-0066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lidz CS, Peña ED. Dynamic assessment. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 1996; 27(4):367-72. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461.2704.367 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McGregor KK, Williams D, Hearst S, Johnson AC. The use of contrastive analysis in distinguishing difference from disorder: a tutorial. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 1997; 6(3):45-56. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360.0603.45 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Paradis J, Emmerzael K, Duncan TS. Assessment of English language learners: using parent report on first language development. J Commun Disord 2010; 43(6):474-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.01.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McLeod S. Multilingual Children’s Speech. Bathurst, Australia: Charles Sturt University; 2012. Available from: https://www.csu.edu.au/research/multilingual-speech.

- Law J, McKean C, Murphy CA, Thordardottir E. Managing Children with Developmental Language Disorder: Theory and Practice Across Europe and Beyond. Routledge; 2019. 10.4324/9780429455308.

- Vukic A, Gregory D, Martin-Misener R, Etowa J. Aboriginal and western conceptions of mental health and illness. Pimatisiwin 2011;9(1):65-86. Available from: https://journalindigenouswellbeing.co.nz/aboriginal-and-western-conceptions-of-mental-health-and-illness.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5TM. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: APA; 2013.

- Caesar LG, Kohler PD. The state of school-based bilingual assessment: actual practice versus recommended guidelines. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 2007; 38(3):190-200. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2007/020) [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Guiberson M, Atkins J. Speech-language pathologists’ preparation, practices, and perspectives on serving culturally and linguistically diverse children. Commun Disord Q 2012; 33(3):169-80. doi: 10.1177/1525740110384132 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Peña E, Iglesias A. The application of dynamic methods to language assessment: a nonbiased procedure. J Spec Educ 1992; 26(3):269-80. doi: 10.1177/002246699202600304 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jordaan H. Clinical intervention for bilingual children: an international survey. Folia Phoniatr Logop 2008; 60(2):97-105. doi: 10.1159/000114652 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kritikos EP. Speech-language pathologists’ beliefs about language assessment of bilingual/bicultural individuals. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2003; 12(1):73-91. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360(2003/054) [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McLeod S, Baker E. Speech-language pathologists’ practices regarding assessment, analysis, target selection, intervention, and service delivery for children with speech sound disorders. Clin Linguist Phon 2014; 28(7-8):508-31. doi: 10.3109/02699206.2014.926994 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pascoe M, Norman V. Contextually relevant resources in speech-language therapy and audiology in South Africa--are there any?. S Afr J Commun Disord 2011; 58:2-5. doi: 10.4102/sajcd.v58i1.35 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan CA. Evidence-based practice in communication disorders: what do we know, and when do we know it?. J Commun Disord 2004; 37(5):391-400. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.04.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Verdon S, McLeod S, Wong S. Reconceptualizing practice with multilingual children with speech sound disorders: people, practicalities and policy. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2015; 50(1):48-62. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12112 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]